04 Sep Weight Management and Free Flight Bird Programs

When I first started flying my parrots with my mentor Dean in the year 2000, I had never heard of weight management. Our version of creating motivation was flying before meal times and perhaps keeping a light dinner prior the parrot’s first flight and training before breakfast. I had never heard of reducing a free flying parrot’s weight and wouldn’t even think of it as a long-term strategy. We used our birds’ preferred foods for recall and varied our reinforcers often.

Fast forward several years to my first professional bird trainer, I found to my surprise that parrots were trained for their pelleted diet, weighed every day, and everyone had their diets weighed out to the gram. Parrots did get seeds and nuts as reinforcers, but these were extras and they largely worked for the bulk of their diet.

Weight Management as an Industry Standard

As I continued at other zoological institutions working at free flying bird programs and connecting with other professional free flight trainers, it was clear that this was the industry norm. In some cases, weight management was a tool utilized for problems like biting and other forms of aggressive behavior in an effort to make it easier for a wider range of staff members with varying degrees of experience to work with a large team of program birds.

What began brewing for years and started as a leaping off point in 2013 was the idea of building an organization with one of the primary goals to be learning more about weight management (or lack thereof) and how it shaped the free flight education experience. I wanted to build a safe space where ideas could percolate and experimentation could occur, and eventually, the shape of the education program might move away from the fast and furious twenty minute programs that dominated the education circuits. Thus, Avian Behavior International was born and with it came many challenges and triumphs and even more questions.

Two Components of Weight Management in Animal Training Today

Questions about weight management are not new, and if you go on any falconry forum (or don’t; that wasn’t a suggestion in good faith) and you will see plenty of discussion about falconry birds and weight management. Differences in opinion exist, as they often do, that largely have to do with the experience of the falconer and the way the bird is flown.

For the purposes of this paper, of critical importance is to define weight management: the purposeful rationing of food that results in the reduction and management of an animal’s weight and/or body condition in order to increase motivation to achieve a desired response. Whether or not the weight is being monitored through the use of daily weighing is irrelevant to this definition. This is not Schroedinger’s cat; if the bird is hungrier, we can guess he weighs less.

Weight management is not inherently starvation. I would argue that for the most part, many animal and human diets are managed to certain degree, particularly for health reasons. It is the clause that we are increasing motivation to perform a desired behavior that weight management can go too far. Animals in the wild don’t eat every day, often as part of their natural state of being, as is the case for some species.

Many great points were brought up in Barbara Heidenreich’s 2014 paper on ethical considerations of weight management. As our work here and other’s was referenced, that makes a great resource for people wanting to learn more about the concept. As such, it has been my experience that we are still seeing the same issues with weight management, perhaps only a bit more public now. Therefore, the conversation has taken on two components:

1) the original discussion of the dangers of severe weight management and

2) whether or not weight management is being used at all.

For this paper, we are going to differentiate between severe weight management and weight management, and we will get into the why’s in just a moment. At some point on the weight management continuum, one must assess whether the delivery of food trending towards the extreme end is truly positive reinforcement or negative reinforcement. In the process of positive reinforcement, an individual uses his behavior to work toward an outcome it values. With negative reinforcement, the individual uses his behavior to remove an aversive. However, I have observed conditions in which the state of hunger was so high there are strong indicators where food no longer exists as first and foremost a consequence to work toward but a way to relieve an aversive set of antecedents.

Severely weight managed birds display a variety of conditions when on a working diet, such as:

- being unable to molt

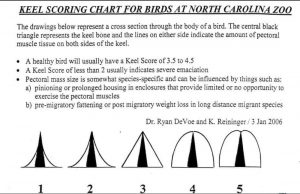

- an unhealthy body score (See keel scoring chart below)

- consuming inedible objects regularly

- gorging on water just to feel a full crop

- refusing to bathe

- little to no preening or resting on one foot

- needing increased supplemental temperature arrangements

- may revert to juvenile behaviors if not an imprint or an extreme version if they are an imprint.

Even when on full diets, they can show increased aggression and can also have a wide variety of physiological effects that result in lack of proper nutrition and can lead to an unhealthy relationship with food for the animal’s life, even if that animal is eventually allowed to be on a normal diet. For instance, I have known a few red fronted macaws that have been strictly managed and will regurgitate their food and eat it again (known as R and R) constantly throughout the day.

Weight Management Discussions Today

Problematically, the very definition of weight management gets muddied by people redefining their actions, much to the detriment of the birds and trainers themselves. Professionals publicly stating that they don’t manage weights when they aren’t monitoring the birds’ weights but still limiting food doesn’t help move the discussion or developments in conservation exhibition forward. Again, just because someone isn’t weighing their animal doesn’t mean they aren’t weight managing it. It just means they aren’t monitoring it.

This doesn’t offer practical advice to new trainers who are told that others aren’t using weight management. In fact, just the opposite. It offers an inaccurate and incomplete framework for a redefined training term, unbeknownst to the rest of us. If the lexicon doesn’t provide for a convenient term, then practices should still be explained thoroughly.

There is much nuance to appetitive drive, some of which we will discuss later in this article, though much of which is left to learn. Continued discussion on this topic is important for trainers to explore without setting themselves, their birds, and their team up to fail or live unhealthy lives filled with stress no matter what their management regimen is.

Clunky and unsafe weight management practices persist for a few different reasons:

1) Weight management like punishment, gets results, and thus becomes very reinforcing to for the trainer. It’s easy to use and thus, easy to abuse. It does not take a lot of finesse in order to get results and the fallout is not easy to connect action

2) Amateur trainers are learning this tool and teaching it to others without understanding other forms of motivation and the short- and long-term exposure of risk that weight management can create.

3) It takes a paradigm shift to exhibit education birds in a different way. One cannot simply feed birds more, or they would understandably lose their bird. More on this below.

4) The definitions are starting to get very slippery as trainers try to get extremely granular with their practices.

Addressing these issues head on is the only way we as trainers can have open and honest discussions and move our practices forward. It’s understandable that the emotional quotient of such topics would be high; I have personally sat in on meetings and been on the receiving end of some intense fear surrounding it. But to not acknowledge that animals can be just as at risk to problems with too much weight management as too little is to put our own emotions in front of progress in the name of wellbeing.

Developing a Philosophy

Moving toward a more progressive form of weight managing free flying birds for me with ABI, if it was used at all, came over time with some major puzzle pieces being put together

- Education Programs can evolve to fit the vision

- The animal must be rewarded well for the job it completed

- Manage weight as a last resort

- Birds must molt and have good body condition in working condition

- Early socialization and training are key components to strong ambassadors

- Birds maintain a healthy relationship with food

The industry standard, as studied and measured at least in the US, is that education programs should be 22 minutes. In 2012, I took a family trip to the UK and of course, took in a falconry demonstration at a castle. The falconer was incredible and presented with three birds for fifty minutes. The audience was completely engaged. The birds, a Bengal Eagle Owl, Harris’s Hawk and Gyrfalcon were stuffed to the gills and flew amazingly all over the grounds (okay, well not the owl) and so close to the people. He had volunteer after volunteer come up for some up-close action. I came away inspired and refreshed. I know the trend is perhaps moving towards more and more, and at the time, even I had a packed show of nearly 30 birds in less than 30 minutes. But I still have my notes from that day, and it still moves me.

This experience, along with how I knew to raise parrots from my early college years, became my budding ethos. One cannot expect to be able to work a hawk for very much food if it is on stage for less than a minute with less flights than you have fingers on a hand. Not only are we doing the bird a disservice, but the audience as well. Another bird trainer and educator once told me that she too thought we aren’t giving our audiences much credit, that you can teach an audience to engage in the program length we want them to, it’s all in how we present the subject.

One also needs to take into account the birds’ ethology when designing a flight program of any kind and base expectations from there. Parrots in the wild don’t typically fly from point A to B for every flight, they usually have wide loopy flights. Expecting tightly controlled flights as a matter of routine generally takes controlling appetites for a well-fledged parrot.

Birds of prey differ from one another greatly in flight style. I have been asked a few times how to increase response time for owls. Owls fly differently than hawks because they have evolved to be a different predator. There are ways to increase their response time up to a certain point, but to ask most owls to fly the same way from one point to another than one is asking a hawk is unnatural and thus, most likely looking for an unhealthy level of motivation. One must be able to assess the risks of too slow and too fast for any bird.

In the wild, some vultures will eat so much that they can’t fly and will not eat for several days afterward. Some days birds of prey will crop up and not need to eat every day. These practices may be challenging if not impossible to safely replicate in human care, but can we use these adaptations to help enhance motivation and further, the education experience?

Early Raising and Socializing

To fly our birds in a different way, it means we have to think about how we raise them. At ABI, we start early with many of our species, teaching them to step on the hand or glove for baby food as soon as they are able and keeping it safe for them always. We teach the babies to run and fly to us for each meal so that they always see coming to us as an action of value.

We shape other behaviors early on as well, from husbandry behaviors such as nail filing, foot and wing touching, crate training, stationing, toy playing, stepping on new people and going outside. We socialize them heavily by taking them to our outreach programs and learning about crowds and traveling in cars. All of this makes their training fun, easy, and continuous. As they get older, the birds of prey that we do work with as nestlings, like owls and vultures, need less weight management because they have this strong foundation ingrained in their upbringing.

Our Take on Weight Management and Free Flight Birds

At ABI, we have a very fluid relationship with weight management. Some birds we don’t manage at all, like our parrots. Our meat-eating birds, like vultures, raven, ground hornbill, falcons, owls, and hawks all have ranges under which they will work. This eliminates the need for a specific target weight and for diets to be measured to the exact gram. These ranges are always within a window they can safely molt in, so we know they are at a healthy weight. We also feel their keel and thighs for body condition scoring. As of summer 2019 of this article writing, every one of our birds has molted or is still molting and in working condition, flying offsite and on.

For our birds of prey, we employ a method I call feast and fast, or rather heavy food days and lighter food days, as true fast days are rare. Feast days are days worth working hard for, so that they associate these days with powerful food motivators. We arrange training and programs days with food schedule, but even if the bird works every day, we can still have shorter training sessions and longer ones. This mimic a wild raptor would eat, where food and flights aren’t set at a constant. In this way, our ranges can be 10-50 grams for some of our raptors (not micros), and we don’t have to measure our food to the gram.

Our parrots and other non-meat eaters hardly if ever see their weights changed. We utilize early socialization and training, food management and diet delivery (i.e. timing of meal delivery), strong secondary reinforcers, and variety of reinforcers to build strong free flight reliability and keep cue latency to a minimum. If they need to do a side project for any reason, a small temporary tweak in diet amount makes a huge impact because they are so accustomed to have as much food as they can eat.

Because of the specific way we train birds, particularly for free flight, this also means that I do not, nor do I recommend, pulling any parrot out of an aviary and training it. To that point, nor do I train someone else’s heavily managed parrot that has only known motivation through the reduction of food in order to achieve free flight success. Taking a bird that has been previously clipped, not allowed free flight at an early age, and/or heavily managed and expecting it to

adapt to the paradigm to which I manage my specifically managed birds is asking for failure and frustration in both trainer and bird. While exceptions occur, understanding how important the developmental period that allows for brain development and learning history is critical for the success of your training program. Ambassador parrots that don’t have a lot of skills and were largely trained to fly from Point A to Point B I would likely not train to fly like mine and may consider either not free flying in order to keep the bird safe or keeping them on a healthy weight management plan that allows for the building of skill if that bird is a qualified candidate.

Considerations Before Manipulating the Bird’s Weight

There is a science behind weight management, both in how you motivate an animal and why. Here is a list of the main questions that we go through, though there are plenty more that are specific to the situation at hand.

- What else have I tried?

- What is this bird’s learning history?

- Am I asking for something appropriate to this bird’s ethology?

- What species is it, and thus what behaviors is it likely to access?

- Is it an imprint?

- Does this bird fly free, does it fly indoors or stay on the hand?

- How does the bird act around food?

- What level of fear response am I getting and how long has it been practicing it?

Understanding your bird’s ethology is something that is very important to how much motivation is needed to complete the behavior asked. Like the owl example referenced earlier, some behaviors in educational programs are considered natural or can be shaped through early socialization experiences, and some defy the bird’s natural behaviors. There are numerous examples of these seemingly small details that we ask of our education ambassadors because it fits into what our needs are for the amphitheater space or our particular vision for the program.

Weight management is a complex topic, as appetitive drive is inextricably linked with learning history and natural behaviors. As important to recognize the fallout of severe weight management is grow as a trainer and consider all of the tools that one has when connecting with their animal ambassador coworkers.

For more on the subject

Become a Premium Member of the Avian Behavior Lab!

Weight Management in Animal Training: Pitfalls, Ethical Considerations and Alternative Options

Barbara Heidenreich 2014

The Flying of Falcons

Ed Pitcher and Ricardo Velarde