13 May I Found a Wild Animal, What Do I Do?

I found a baby wild animal all by itself, what do I do? Would you believe me if I told you we see this question everywhere, and it breaks my heart when babies are “saved” unnecessarily. Now for a bold statement: if we love wildlife and want to see the wildlife that coexists among us thrive in their natural habitat, leaving wild animals alone, even babies, should be the default response under most circumstances.

The desire to help another being in need is completely relatable, and as animal lovers, many of us feel a sense of duty when we find wildlife in what looks to be a predicament. After all, human encroachment and activity has already endangered lives, species, and whole ecosystems, shouldn’t that obligate us to take action when we find an orphaned animal? The truth is quite a bit more complicated and without the right information, it’s hard to know what the best thing for that animal is.

Why We Intervene with Wildlife

The problem is, wildlife rehabilitation centers everywhere get overwhelmed by the amount of needlessly orphaned wildlife due to direct human intervention every year. These challenges are compounded by:

- A basic misunderstanding of how wild animals learn to survive and the resources it takes to raise them

- A lack of knowledge about ecology and

- Saturation of social media posts, even by world renown scientific magazines, showing human led intervention

Finding a baby rabbit, owl, songbird, or deer on its own can be incredibly heart wrenching. Surely it’s in danger and will succumb to a horrible death. It can’t fend for itself against predators or will run into trouble in some other way. Well-meaning passersby swoop in, remove the animal from the wild, and contact someone licensed in wildlife care after they have already disturbed the wildlife.

How Wildlife Raises Their Young

For wild mammals, such as rabbits or deer, babies will often tuck in little nests in the grass or brush. They instinctually sit tight to the ground and do not move while she leaves them on their own and forages for herself until the youngsters are strong enough to follow along. They have different coloring to help them blend in to their nest sites. Fawns are born scent free and have poorly developed scent glands. The doe cleans them of their feces and urine constantly and moves their nests sites to evade detection by potential predators.

Baby rabbits will often be in a nest in open spaces because even predators don’t like to be out in the open. They are covered with thick grass and fur. If they are in a yard, it’s best to mow around the grass nest instead of moving it. Keep dogs and cats away from the nest. Mother rabbits do not sit on a nest like birds, and it’s very rare to find an adult rabbit at the nest during the daytime. They only return at night if no one is watching. Even if it is raining, the nest is protected and designed against the elements. Wild rabbits do not survive well in human care, so avoiding taking them from the wild is of utmost importance.

Branching Baby Birds

Baby birds are often found on the ground after venturing from the nest, falling out, or trying to branch. The “branching stage” is the point at which birds are just about ready to fledge and can flap and hop from branch to branch as they finish developing feathers and muscles for flight. Just like any juvenile, the learning process takes a

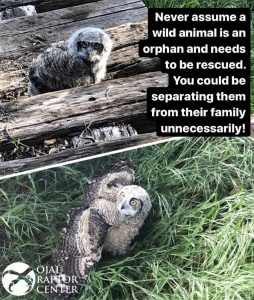

PSA from the Ojai Raptor Center encouraging people to think twice before unwittingly separating owls from their families

bit of trial and error, and sometimes those errors end up with them falling to the ground. The parents will continue to feed and protect the bird on the ground. Songbirds and raptors including great horned owlets, barn owlets that can’t be re-nested or returned to their original nest or a box, flower pot or berry basket near their nest will still be fed and even protected by their parents on the ground. This is part of a natural process that happens whether or not humans are around. Birds are designed to develop very quickly because the fledging process is fraught with so many mistakes, that they won’t have to be hop-flapping for very long. Even great horned owl babies (owlets) can climb trees and get out of harm’s way remarkably well.

Baby birds that are taken into rehabbers run the risk of becoming imprinted on people. Once they see humans as a source of food, they cannot be returned to the wild. A human imprinted animal in the wild can easily make itself a nuisance as it grows up, can fight humans for territory or resources, and most certainly will get killed by dogs, cars, or other humans. Great horned owls very easily imprint on humans, as do turkey vultures. Turkey vultures often nest in rocks or abandoned sheds and are very easy to “rescue.” ABI has Dallas, a turkey vulture that came from such a situation. While she is a great education ambassador for her species and cause, having more vultures doing their job in the wild is always a benefit to the environment.

Wild Parents are the Best Parents

Increasingly, research is showing how critical parental guidance and mentorship is for the survival of young. Dispersal after weaning can happen much later in many species than originally thought, with offspring hanging around the parents in some species of animals for up to a year, learning how to hunt and fend for themselves. Imprinting on any humans should be avoided at all costs, and responsible rehabbers use surrogates, “nurseries” (raising babies of the same species together so that they will learn from and embolden each other), costumes to mask the human form, and puppets to help feed the babies.

What To Do and When To Intervene

If you find a wild animal, one that is potentially separated from its parents, the best thing is to always try to leave it alone. More than likely, it will be fine on its own. If you feel that you must do something, contact a licensed rehabber before moving or touching any wild animal. A responsible, ethical wildlife rehabber should always be to see if the animal can be re-nested or left alone first and foremost. Unless the animal is covered by ants, visibly injured, or is naked and at risk of exposure, leaving it alone for the parents to care for it or a wildlife professional to assess is its best chance for survival.

Getting accurate information out to people who want to do right by wildlife helps everyone in the long run. There are numerous social media outlets, both of social influencer origins and even high profile, well-regarded scientific magazines, celebrating the intervention of wildlife led by humans. This promotes unhealthy environmental practices that upsets delicate ecological balances.

The Social Media Factor

Many social media outlets are designed to grab attention, pull at our heartstrings to enhance engagement, and portray small bites of edited information, often with happy and heroic endings. But if these articles and videos are actually true, they don’t always do a great job of conveying the complexity of wildlife issues. The decision of whether or not to intervene with wildlife at risk is actually very challenging, and in many cases illegal. There was a story in 2016 of some visitors that found an American Bison calf in Yellowstone National Park, and “rescued” it by putting it in the back of their car and bringing it in to Park Rangers. The animal could not be returned to the wild nor sent to a zoo or education facility (biosecurity testing for brucellosis and other transmissible diseases was cost prohibitive) and was then euthanized.

Why We Make Animals Unhealthy

Many people happily feed the wild animals that live in yards and public spaces, enormously impacting the health, welfare, and behavior patterns of wild animals. Not only is human food usually unhealthy for animals, but the desensitizing of wildlife to human presence does not end well for them. A wild animal that seeks humans for food

Social media post of someone who means well but isn’t informed on how to interact with wildlife. It’s very common to see how people want to connect with wildlife, and don’t mean harm. Some animals are meant to be interacted with in this way, it does more harm than good.

will often find itself in the middle of traffic, in a tangle with pets and livestock, or getting shot in the name of protection or (legal or illegal) recreation as they approach the wrong human looking for resources. Teaching wildlife that humans are a safe resource only satisfies our individual fantasies and usually ends the animals’ premature death.

It’s easy to see why accepting nature on nature’s terms is so difficult when all around us are stories of scientists and experts intervening in this way. Even National Geographic shows stories of nature guides breaking policy and illegally intervening with weakened animals on wildlife reserves without offering a much-needed narrative as to why that particular decision was made. This sends a disappointing message that when nature is not as swift and decisive as we desire, we must take action. Predators and scavengers play a very vital role in a keeping a healthy balanced population, and whether or not we humans meddle in the affairs of nature, there will always be suffering on many different levels. When we rob an animal of a meal or keep a wild animal alive that was not meant to stay in the gene pool, these interventions can actually create more problems for an already delicate ecosystem.

Loving Animals Means Leaving Be?

This is the dangerous side of anthropomorphism: attributing human characteristics to inhuman beings. No one wants to see suffering, lost or “orphaned” young, the killing of one being for the benefit of another. But treating wild animals as if they have human needs is not an accurate reflection of the incredible adaptations they have, but how easily we can injure them. Many of us want to identify ourselves as a champion of animals, a warrior for wildlife. Loving wildlife and wanting animals to thrive in their own homes takes information and understanding, not just compassion and empathy. Coexisting with the native species in our communities takes an effort. Many zoological and educational organizations, state and municipal nature parks, museums and other educational facilities strive to offer informational opportunities to help people who want to learn do well by local native species.

For the natural world to exist, we have to educate ourselves in methods that foster the resilience of animal adaptations and allow for life of the hawk, the coyote, the songbird, the owl, and the lion to continue in the midst of the developed world. Nature is neither forgiving nor fair. It is opportunistic and shrewd. Nature does not adhere to the laws of morality, good and evil, naughty and nice. It exists, whether we appreciate its indifference or not. The more we leave wild animals – even babies – to learn the laws of their fast-changing world, the better equipped they are to survive.

Resources

Our other blog post on helping young wild birds is right here

https://www.ojairaptorcenter.org/

http://www.vetstreet.com/our-pet-experts/what-should-you-do-if-you-find-a-bunny-nest

https://rabbit.org/faq-orphaned-baby-bunnies/

https://blog.nwf.org/2015/04/finding-a-fawn-what-to-do/

https://www.nativeanimalrescue.org/understanding-deer/

https://www.wildlifecenter.org/human-imprinting-birds-and-importance-surrogacy

https://ecosystems.psu.edu/research/projects/deer/news/2015/deer-don2019t-touch-that-baby