15 Feb The Dangers in Over Cuddling Baby Parrots

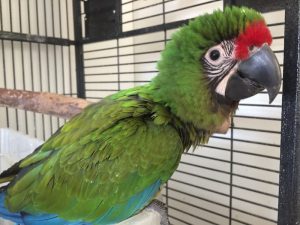

Getting a new baby parrot is a wonderful thing. Some babies, like macaws, are particularly smooshy and lend themselves well to gentle puppy-like play, head and tummy rubs, and even idle snuggles while we watch the tube or work at our desks. Indeed, this seems to elicit soft groans and gronks of pleasure and contentment. What better way to cement the human-animal connection?

Unfortunately for our primate needs to touch, feel, and pick fleas, these habits and activities early in our relationship with our baby parrots is actually setting us up for some massive problems down the road. We are going to get really granular on those challenges are, why we see so many people – even professionals – doing them, and how we can interact with our parrots for long term success that is mutually beneficial.

What we are referring specifically to is overall body touching, under wing rubs, prolonged (more than 10 seconds or so) head  rubbing, flipping over on the back and playing with the parrot’s tummy and feet, and beak wrestling. This level of tactile interaction often leads to the parrot going into what I have termed a very floppy state, scratching its own head, standing on its wing, fluffed head feathers, head bobbing, wing flipping, baby begging for an extended period of development, sometimes only prompted by the vicinity of a human friend or mere eye contact.

rubbing, flipping over on the back and playing with the parrot’s tummy and feet, and beak wrestling. This level of tactile interaction often leads to the parrot going into what I have termed a very floppy state, scratching its own head, standing on its wing, fluffed head feathers, head bobbing, wing flipping, baby begging for an extended period of development, sometimes only prompted by the vicinity of a human friend or mere eye contact.

Macaws in particular lend themselves very well to these kinds of interactions, and I have worked with a few blue and gold macaws that even raised with their siblings and minimal handling had a prolonged state of baby behavior in that they were quite floppy. I have also seen several teen-aged macaws of various species that were raised from day one by humans that continued some maladaptive, adjunctive behaviors. In many cases, these parrots were the product of the “purchasing unweaned so we can bond” era of parrot companionship, much of which proliferated in the 90’s here in the States.

The truth is, while some type of puppy-like behavior is somewhat normal in pre-fledged nestling parrots in the wild, most of our interactions aren’t typical. And while many parrot species do spend an extended juvenile stage learning from their parents before starting their own families, the way that our close immersive family units are with them are not particularly natural.  What would be natural is for them to be learning with their parents and spending some time apart as well. And while our goal needn’t be – nor could it possibly be – to replicate their relationships in the wild, as parrots are capable of adapting given the right parameters, it is important to understand how early interactions can lead to certain habits later in life.

What would be natural is for them to be learning with their parents and spending some time apart as well. And while our goal needn’t be – nor could it possibly be – to replicate their relationships in the wild, as parrots are capable of adapting given the right parameters, it is important to understand how early interactions can lead to certain habits later in life.

First, it is generally pretty normal for us humans to want to smoosh, cuddle, and in general be quite tactile with objects, animals, and even other humans. As someone who spends their general career orchestrating connections and fostering support for conservation programs through free flighted programs, my encounters with the general public and the birds I work with range from the toddler racing up with the outstretched arm to the glaring falcon to the awestruck strong, silent type who sheepishly asks “Can I pet your owl?!” Petting things is how we want to interact with our world.

So me telling others that smooshing the puddle of a macaw who wants nothing more than to stick her feet in the air and be smooshed for hours doesn’t exactly make me your popular neighborhood parrot behavior consultant. And then saying, you’ll be calling me in a couple of years isn’t exactly the warning signal I wish it were!

What exactly is the harm in snuggling parrots for long periods of time, creating these puddles of macaws or sooky cockatoos that are babies and desirous of our attention? As a behavior consultant, I have long maintained that babies of any species

naturally take more attention as they don’t have a lot of life skills. But that is the important nuance to recognize: they need life skills and it is our job to provide them with that. To associate our presence with the opportunity to snuggle most of the time is not setting them up for success. In fact, it is creating complicated patterns for a future of inappropriate and confusing pair bonding which is not healthy. This further proliferates that concept that parrots are one-person birds and incapable of having relationships with others.

The other problem with creating a highly tactile relationship with young parrots is that it can lead to seeking automatically  reinforcing behaviors (often called self-reinforcing behaviors in the lay community). What this means is that by offering snuggles, cuddles, scritches, and scratches regularly, we create patterns and habits in their behavior that become lasting expectations. The flood of feel good hormones that comes these interactions can conceivably become triggered at the slightest hint of cues, such as a visual cue (they see us), audio cues (we return home), and in the absence of the outcome we usually offer them (those delicious rubs), they achieve it themselves or could potentially intensify seeking behaviors to achieve the desired outcome!

reinforcing behaviors (often called self-reinforcing behaviors in the lay community). What this means is that by offering snuggles, cuddles, scritches, and scratches regularly, we create patterns and habits in their behavior that become lasting expectations. The flood of feel good hormones that comes these interactions can conceivably become triggered at the slightest hint of cues, such as a visual cue (they see us), audio cues (we return home), and in the absence of the outcome we usually offer them (those delicious rubs), they achieve it themselves or could potentially intensify seeking behaviors to achieve the desired outcome!

The truth of the matter is, a pair bond with our parrots is neither healthy, humane, nor appropriate for us to foster for the decades of lifespan we intend to share with our parrots. It is a far richer existence for us to support strong relationships with multiple household members. Not only is this safer and less stressful for the humans, but it also means the parrot won’t feel it needs to defend its partner vigorously against all of the perceived threats. While it may seem funny to us when a one or two pound parrot goes charging after one hundred and fifty pound interloper, the sense of obligation the parrot feels is very real, and we cannot understate the biological drive that is pushing him or her to do so.

So is the answer then to just refrain from all snuggling, like a complete killjoy? Are we only bound to a five second head rub “One Mississippi two Mississipi….”? SNORE! Who is going to do that?! While it is generally better to stick with brief and generally infrequent head scritches to avoid pair bonding, there are a few things that we can do when our young birds are in their baby phase and enjoy more silly rolling on the back behavior.

First, we want to keep in mind to avoid general rough housing, beak play, and if it does lead to overexcitement, that we stop puppy-like behavior immediately and seek to avoid it in the future. Second, we can pair this kind of play time with more  positive outcomes, while having the parrot let us play and manipulate feet, wings, and even tail feathers very gently. We will also use this time to gentle do brief chest palpations and towel work all while pairing with positive tactile interactions that will allow us set the groundwork for fear-free veterinary procedures as the parrot grows up. It is very important that we stay within the parrot’s comfort level so that we don’t end up sensitizing them to these interactions and that we also maintain this kind of work as the bird grows up to stay consistent.

positive outcomes, while having the parrot let us play and manipulate feet, wings, and even tail feathers very gently. We will also use this time to gentle do brief chest palpations and towel work all while pairing with positive tactile interactions that will allow us set the groundwork for fear-free veterinary procedures as the parrot grows up. It is very important that we stay within the parrot’s comfort level so that we don’t end up sensitizing them to these interactions and that we also maintain this kind of work as the bird grows up to stay consistent.

And finally, balance these interactions with toy play and ambient attention. What this means is that every time you walk into the parrot’s space, you don’t always have to give it direct, tactile attention. You can reinforce a soft contact call or just pass through. Your presence does not always have to mean that something will happen. Life can keep going on as the parrot is playing with its toys or chewing on his food. We want to make sure that we are not interrupters of good behavior.

If you want more evidence based, companion parrot information delivered directly to your inbox without all the fluff, sign up for our email list!

You can also try out a basic annual membership in our Lab for just $3 for ten days with the coupon code TEN